November 22, 2019

gregory eddi jones

One day in Kolodozero, a harsh rural village in Russia’s North, a man showed up from Moscow fresh out of seminary and proclaimed himself the priest. He and his friends set to work rebuilding the village’s church, burnt down decades prior, in hopes to renew faith in this place. Ekaterina Solovieva, Russian-born, and Berlin-based documentary photographer set out to meet this man, Father Arkady, and to befriend him and photograph his intertwined life with the village’s sparse populace.

I can’t place myself in the shoes of those who call Kolodozero their home, but Solovieva’s book, The Earth’s Circle—Kolodozero (Shcilt, 2018) does all it can to make them present. Her pictures breathe the air of this place. She takes us into the homes of these villagers and photographs uncompromisingly in stern black-and-white. What she shows us are people indignant to their barren surroundings, who chop wood and canoe in cold wind, and perhaps who rely on faith, of some kind, to get them through their days. In the book we see families huddled together in small houses, sharing dinner with neighbors, summer leisure, and Easter and Christmas celebrations. All-the-while, there is a darkness that underlies all these moments, an inevitability. And this visual quality of Ekaterina’s work proved tragically prophetic as one man in the book ended up murdered, and the priest himself died, at 45, just days after the book was published. This small, remote place, and Father Arkady’s flock that occupies it represents perhaps the most honest of what we are as humans.

Father Arkady is sitting on the porch of a rural house and basking in the spring sun. Spring 2017.

Gregory Eddi Jones: I want to dive into your project on Kolodozero, which centers on Arkady Shlykov, a priest who moved to the town to rebuild its church decades after it had burned down. Could you talk about how you initially learned about Shlykov and how you came to meet him?

Ekaterina Solovieva: For as long as I can remember, there was an old religious icon hanging on the wall at home. My father found it in an abandoned chapel in the north of Russia when he was young. The stern, dark faces of Our Lady and the Baby always attracted me – as if they were hiding a centuries-old mystery. My father’s stories about his travels into the far villages of the north made me dream of these lands.

I first traveled to north Russia when I was 18 and came back with some sketchy photos. My father looked at them and said I should write about the villagers, that I should take their pictures and tell their stories. So, 10 years later (in 2009) I was moderating a popular internet community “Russian North.” Diverse journalists and photographers were posting there about different topics on Russian northern provinces. I saw documentary pictures from Kolodozero made by Misha Maslennikov. At the same time, I read a story about three friends, saw them in the photos, and was specifically impressed by the punk priest. I thought it would be great to get there one day.

In the summer of 2009 my friend, who had known farther Arkady personally, proposed that I accompany her there. I agreed and that trip changed my whole life. We got into the middle of an incredible activity: two artels of icon painters were painting the ceiling of the church. I got up the scaffold and saw farther Arkady there – in a torn t-shirt, with sawdust in the beard, and with a burning gaze. A week passed by like a single day. By the time I was leaving it was clear that this place and farther Arkady himself, with whom we immediately became friends, caught me very tightly. I knew I would return. I could feel the ambiance, and I remembered my father’s words.

Drunk “local celebrity” Yurka at the priest´s house. May 2014.

A cow seeking escape in the river. Summer 2012.

GJ: What a fascinating story! You mentioned you became friends with father Arkady immediately. What kinds of things would you talk about with him, and how did you bond with him so quickly? And did you take that first trip up knowing that you wanted to make photographs?

ES: Before meeting father Arkady, I learned a little about him from publications on the internet and from our mutual friends. I knew that he had a passion for punk music from his youth and was himself a punk in his way of life. He listened to the same Russian punk band as I did, a Siberian protest punk-rock band “Grazhdanskaya Oborona.” The leader of the group, Yegor Letov is very popular in Russia. Arkady was friends with one of the band’s musicians and even worked part-time as a bouncer at their concerts.

The first day we met, I helped Arkady and his friends paint the ceiling of the church. We used to joke, laugh, and talk about all sorts of things. He turned out to be a very easy and open person in communication. In the evening we watched a documentary about Jim Morrison, whom Arkady loved no less than Yegor Letov. Then we talked about different books and writers.

When I first went to Kolodozero, I brought a digital camera and a film camera with me. I made a short digital report for a church magazine and shot one roll of film. And so, when I developed this film, I realized that I wouldn’t make digital photos anymore, but I would do a long-term project about the Kolodozero and father Arkady. On the first roll there was nothing special – houses, people, cows wander in the rain… But there was some special atmosphere that fascinated me and I loved this place forever.

Viktor and Elena, singers in the church, clean up after the service. Summer 2016.

Village resident Uncle Pasha shares an anecdote. Spring 2013.

GJ: I’m curious to learn more about the atmosphere of the town you speak of because the village of Kolodozero itself is such a focus of your book. Many of your photographs illustrate the day-to-day lives of the people in this town. Did it take long to gain their trust? And what was life like as you lived among them?

ES: That’s a very important question. The fact is that my guide to the people living in Kolodozero was Father Arkady. He introduced me to several locals. We went to visit with him, drank tea with people, I listened to the endless stories about Kolodozero. And literally on my second visit,the residents knew very well who I was, where I was from, and that I was a friend of father Arkady, helping him with his household. It was not a problem for me to live in the village: I have been familiar with village life since childhood – I know how to cut grass, cut firewood, sink ovens, work in the vegetable garden, pick berries and mushrooms, fish. Not only do I know how to do it, but I also love all this absolutely sincerely. Also, and therefore, apparently, I immediately became “a local” in the Kolodozero. The locals stopped noticing the photographer in me almost immediately. We went to the forest together, fishing, and so on. I still remember my life in Kolodozero as moments of absolute happiness.

Priest Arkadiy is pushing his guest, Vera, in the courtyard. Spring 2013.

Christmas morning in Kolodozero. Winter 2015.

GJ: What sort of change do you think occurred in Kolodozero after Father Arkady arrived and assimilated himself in the community? I assume the town embraced his presence just as they embraced yours? What do you think he meant to the community during his time there?

ES: It’s a difficult question that’s not easy to answer. When Arkady and his friends started going to Kolodozero, they were very young, about 25 years old. Arkady was a very friendly man, he immediately met everyone and became friends with many people and became his own in the village. Even after his ordination as a priest, many villagers did not perceive him as a priest. He stayed their days as a “cheerful Arkashа” with whom to drink and have fun. This served a bad service, the Russian people needs the priest to be better, cleaner, more holy, and more authoritative. And Arkady was too kind and free – he did not want to establish power and his own orders over anyone. He just lived, helped others, gave himself away and demanded nothing in return. Maybe that’s why there was no permanent community of Kolodozero residents. In another village, Shalsky, where he was also a priest – the community was more united, he was loved there as a priest – maybe because people did not know him as a young man.

A couple of years ago, while walking around the village, I met a local ambulance driver. He told me they didn’t go to Father Arcady’s church. I asked why. So he likes to drink! I replied: that’s how you drink too. To what he objected – Arkady is a priest! He should be better than us. And Arkady didn’t want to be better or seem that way.

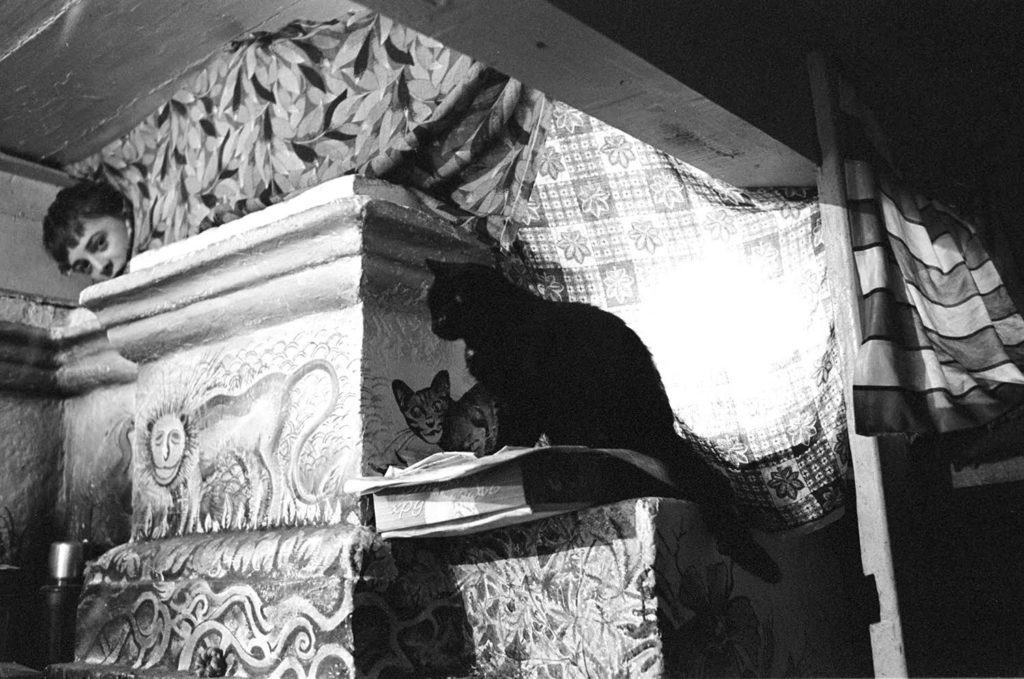

Pashka and the cat are warming themselves on the Russian stove. Autumn 2012.

Father Arkady baptizing a child. Summer 2014.

GJ: In looking through the images in your book, much of the work is rendered with harsh contrasts. Some works are produced with decidedly imperfect technical qualities. I find blown-out skies, motion blur, tilted frames, and these strategies sum up to a characterization of Kolodozero that is quite tense and anxious. The lives of the people you depict seem harsh and unforgiving, as if at any moment everything may come undone. When you set out to document this place did you mean for the work to hold such dark undertones?

ES: Amazing, Gregory, you’re asking the most important questions to understand the book! I will tell you in order why the high contrast and dark tones in the photos are related to my perception of the place. When I started going to Kolodozero in 2009 and shooting there, I was in the beginning of my career. I could say that I was a naive girl who saw the world in pink tones. At first, it seemed to me that I was shooting a positive fairy tale about a strong man who became a priest. But over time, when I became more aware of what was happening in Kolodozero, I became closer to Father Arkady, I realized that his life and the life of the village was not a fairy tale, it was not idyllic. It was a harsh reality where there was loneliness, misunderstanding, and depression.

My visual language began to change rather unconsciously. When I approached the creation of the book in 2016, I reviewed my archive, shot over the years in the Kolodozero, and saw that the photographs of recent years are much tougher. Already at the stage of selection of photos, the editor Anna Zekria joined me in the creation of the book and I told her about Kolodozero, how hard it was for Father Arkady, how hard it was for him to burn out, that he was not understood by the locals. It also influenced the selection of photographs in the book. It was Anna who took away the dark and blurred photos – I rejected them. But they were the ones who created the atmosphere of vicious, vicious reality.

As for the contrast, I told the publisher at once that deep black in the photos is very important for me. When I printed it, they understood my demand a little literally. And the first time I picked up my book, it seemed too gloomy and strange to me. I didn’t know what to do with it. After all, my silver gelatin prints are much softer.

Four days after the book was published, Father Arkady died… And this complicated story finally ended, and then I realized that the high contrast and dark tones, cloudy images were not accidental … As if something was leading me to the creation of a book from above, warned me about the tragic end.

Girls sitting on the bridge across the river Viksenga. Summer 2016.

View on the Church of the Nativity of the Virgin in Kolodozero. May 2014.

Tatiana sitting in a bathhouse with a view of the Church of the Nativity of the Virgin in Kolodozero. August 2014.

GJ: It’s really sad to hear that Father Arkady passed away just four days after the book was printed. He was still young, wasn’t he? What were the circumstances of his death? And did he get the chance to see the book or any of the work from this project? I can’t help but think that this book now exists as a testament to his life, would you agree?

ES: That’s the way it is… The book came out of the printing press on February 8, 2018, and on February 12, Father Arkady was gone. Circumstances of his death are gloomy enough – that’s why I was talking about some bad feeling, which guided me in the creation of the book.

In 2016, Arkady brought up a young man, a social orphan, who was abandoned by his foster family. Arkady gave him a place to live and a place to eat, got a job on the farm, supported him in every way possible and helped him. Arkady trusted this guy so much that he asked him to look after the house while Arkady was away. But the guy made a drunken mess of the house and called in criminal acquaintances. One day a local resident, Yurka, stopped by the priest’s house. The whole chapter in the book is devoted to him – Yurka was cheerful and kind. It is not known exactly what happened, but criminal people killed Yurka, breaking his skull with a heavy object. The whole house was covered in blood. Arkady was away when he received this news. He was very worried. In addition, his health was undermined and his heart weakened. Arkady returned to the house flooded with blood, washed the blood from the walls and died the first night – his heart stopped. He lay there for three days – none of the local neighbors dared to enter the house after Jyrki’s murder.

Yes, Arkady saw the dummy of the book, saw the final layout on the computer – 10 days before his death we talked on Skype and discussed the layout and choice of photos. He liked everything. He was very happy for me because he knew how long I was going to the book. He was also a little embarrassed by the fame that came over him.

It’s important to me that the book was published in his lifetime, that he’s alive in the book itself – and yes, it’s probably a kind of will, a kind of immortalized memory of him and his “Earth´s circle” … I am glad that people all over the world found out that there was such a Russian priest who gave himself to serving people.

Father Arkady in his house. December 2011.

Christmas fireworks on Kolodozero Lake. January 2015

Bio

Born in Moscow in 1977, I’ve lived in Hamburg since 2006. My work focuses mainly on the life of simple country folk living in countries of the former Soviet Union. I place a particular emphasis on religious traditions and customs. My first photobook, ПАЛОМНИКИ (Pilgrimage) was published by Bad Weather Press in January of 2014. The Earth’s Circle – Kolodozero was published in April 2018 by Schilt.

Source: In The In-Between

News

The New Yourk Times: Photographing a ‘Punk’ Priest in Rural Russia

Die Zeit: Der Punk als Priester